After mine operators refused to meet with union representatives, the United Mine Workers of America struck the southern Colorado coalfields on Sept. 23, 1913. The miners' demands included union recognition, the eight-hour day, a 10 percent wage increase, the right to elect their own check weighmen, the right to choose their own stores, homes, and doctors, and enforcement of the state's mining laws and an end to the use of armed guards in the mines.

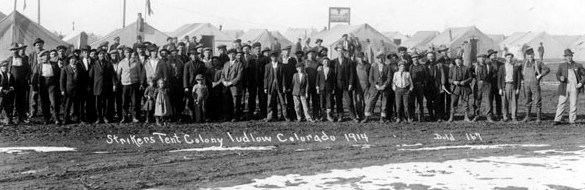

Three major firms led the fight against the union: the Victor-American Fuel Co., the Rocky Mountain Fuel Co., and, the largest coal producer, the Colorado Fuel and Iron Co., a Rockefeller concern. The mine owners began evicting the strikers, who then set up tent colonies on adjacent land. The owners also brought in hundreds of Baldwin-Felts guards, many of whom were sworn in as sheriff's deputies.

After a number of strikers were killed, Gov. Elias Ammons declared martial law and sent in the national guard in late October, but under the command of Adj. Gen. John Chase the guard was used to protect strikebreakers and intimidate the strikers.

Escalating violence culminated in the Ludlow massacre of Apr. 20, 1914, in which at least five miners, two women, and eleven children were killed. In the aftermath of the massacre state labor leaders called on workingmen to arm themselves and organize for self-defense, and a wave of retaliatory violence swept the mining district.

On the request of Governor Ammons, President Woodrow Wilson ordered federal troops into Colorado on Apr. 29 to restore order. During the summer and fall of 1914 the mine owners rejected several efforts by Wilson to settle the dispute, and on Dec. 10 the United Mine Workers called off the strike.