|

The Pullman strike grew out of a conflict over wages paid to employees of the Pullman Palace Car Co. and the rents and other expenses they paid to live in "model" company town. Although wages were cut 25 percent, on average, and hours were reduced after the economy collapsed in 1893, rents remained high. In the spring of 1894 Pullman employees organized a local of the American Railway Union and took their grievances to their employers. But after the company fired three members of the grievance committee, almost 3,000 workers walked off their jobs on May 11; the company locked out the remaining workers. "We do not expect the company to concede our demands," a strike leader noted. "We do not know what the outcome will be . . . and we do not care much. We do know that we are working for less wages than will maintain ourselves and our families . . . . and on that proposition we absolutely refuse to work any longer." After Pullman vice-president Thomas Wickes refused to deal with the union, the ARU's national convention voted to boycott the Pullman Co.: beginning on June 26, ARU members refused to handle Pullman cars. At that point the General Managers' Association (GMA), which represented 24 railroad lines, fired workers who honored the boycott. To retaliate, entire crews walked off the job, turning the boycott in a major railroad strike. |

|

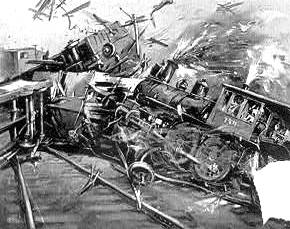

Determined to defeat the strike and destroy the ARU, the GMA established a command center in Chicago and hired strikebreakers to keep the trains running. The GMA also sought the federal government's help, claiming that the strikers were disrupting interstate commerce and the movement of mail: On July 2 federal court judges Peter Grosscup and William Woods granted an omibus injunction against ARU leaders. Then the conflict turned violent. After a riot erupted on July 3 President Grover Cleveland agreed to send troops. The next morning, five companies of the 15th U.S. Infantry marched into Chicago. More troops would follow. In fact by the time the strike was called off on July 17 the federal government had sent over 2,000 men to the city and the state of Illinois had sent some 4,000 militia, and over 5,000 deputy marshals and sheriffs had been sworn in there. |

Home

WEB Accessibility

Created by The Samuel Gompers Papers Project