|

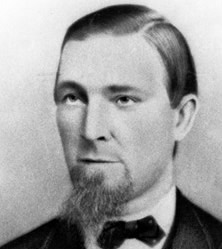

John Siney (1831-1880) was born in Bornos, County Queens, Ireland. His parents were tenant farmers. After their potato crop failed in 1835 and they lost their homestead, the family moved to Wigans, Lancashire, England. By age 7 Siney was working as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill and by age 16 he was apprenticed as a brick maker. Siney later helped organize the Brickmakers' Association of Wigans and served 7 terms as president. Siney immigrated to the United States in 1863, settling in St. Clair, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, an anthracite mining town where he knew other immigrants from Wigans. Employed first as a laborer, and then a miner, Siney participated in a strike to raise wages in June 1864. Although the strike was successful it was also controversial -- the nation was embroiled in the Civil War at the time and coal was essential to the Union cause. |

Once the war ended in 1865 and the market for anthracite collapsed, employers slashed wages 25 to 35 percent. But when they attempted to reduce wages even more early in 1868 Siney and his coworkers called a strike. Over the course of the successful 6-week strike Siney distinguished himseff as a leader: He managed to rent a building to serve as strike headquarters and

raised funds to keep families afloat. He also helped organize the Workingmen's Benevolent Association of St. Clair, a labor organization that would collect dues, pay sickness and death benefits, and provide financial support in case of strikes. (The WBA was renamed the Miners' and Laborers' Benevolent Association in 1870). As president of the WBA, Siney was instrumental in organizing strikes to enforce legislation passed by the state legislature that year that made 8 hours the legal work day as long as there was "no contract or agreement to the contrary." Within two weeks after the law went into effect, some 140 collieries were shut down and by the end of July Siney had helped organize a countywide WBA that represented some 20,000 miners in 22 districts. Elected chairman of the executive board (a paid position he held until 1874) Siney was able to work full time building up the organization. Within a year the various local and county unions within the anthracite region (Schuylkill, Carbon, and Luzerne Counties) had united in a new organization, the General Council of the Workingmen's Benevolent Association. By 1870, 30,000 miners and laborers, around 85 percent of the available work force, belonged to the union. However that organization never lived up to Siney's expectations -- he believed that miners could control their fate by controlling the supply of coal to the market. But since miners tended to put local interests first, they could not be counted on to suspend production to advance their power regionally. That being the case, Siney turned his attention to labor politics. In 1871 he helped organize a labor party in Schuylkill County and in 1872 he chaired the founding convention of the national Labor Reform party that met in Columbus, Ohio. He had not given up on trade unionism, however, and when he got an opportunity to help organize a national union for miners, he took it: In 1873 Siney helped launch the Miners' National Association an organization pledged to shorten the hours of labor, improve mine-safety laws, and promote arbitration as a means of resolving industrial disputes. The MNA also promised to pay strike benefits, if and when necessary. As president of the MNA Siney had few successes -- his own union refused to join the fledgling national union, and the Panic of 1873 took a serious toll on the coal industry. As mine operators throughout the nation began to reduce wages yet again, Siney urged the membership to go slow: Under the circumstances he did not believe that strikes would succeed. Because the membership did not agree -- and forced the MNA to pay strike benefits the treasury could not afford -- the MNA disbanded in 1875. At that point Siney returned to Schulykill County where he bought a tavern, worked as a truck farmer, and started a family. Although he remained active in the Greenback party, serving as president (1875) and vice president (1878) of the national party, he had lost the miners' support. In fact when he died, at age 49, he was reviled as a failure whose conservative policies kept the miners down. It would take almost ten years before Siney's efforts were recognized: In 1887 the Miners' and Mine Laborers' Amalgamated Association raised funds to erect a monument "in memory of his firm devotion to the cause of labor." And over time he would be remembered as the union pioneer whose work paved the way for the United Mine Workers of America. |