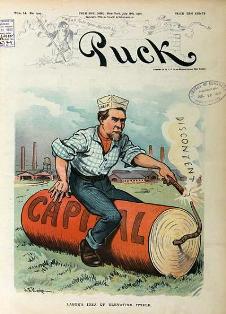

"Labor's Idea of Elevating Itself" (Library of Congress) "Labor's Idea of Elevating Itself" (Library of Congress) |

In an age of ten hour days, subsistence wages, and dangerous working conditions, the idea of organizing an army of labor and achieving justice through strikes and boycotts was inspiring. However there was no guarantee that strikers would prevail. The value of a worker's skill, the ability of a family to survive through hard times, the public's sympathy, and the employer's attitude all made a difference: Some workers, like the bricklayers in Chicago in the late 1880s, won the eight-hour-day after a brief struggle, largely because they were well organized and their local union could afford to pay strike benefits. Others who lacked that advantage could lose everything they had in long, drawn-out, and sometimes violent fights -- including their ability to find another job if they were "blacklisted" by their employers. "Workers understand much better than anyone else the cost of industrial war. They pay the full price," AFL president Samuel Gompers wrote in 1923. "Labor will cease to engage in contests with employers as soon as labor finds it possible to induce employers . . . . to substitute negotiation for contest." |

Created by The Samuel Gompers Papers Project